« IDB “Infrastructure” Funds with an Environmental Twist / Financiamento del BID para “Infrastructura” con Dimensiones Ambientales | Home | The IDB Pushes Ethanol »

Trash Photos XI: A Visit to the Landfill

By Keith R | February 8, 2007

Topics: "Trash Photos" Series, Environmental Protection, Waste & Recycling | 4 Comments »

Someone recently asked whatever happened to my “Trash Photo” series. No, folks, I did not run out of trash- or recycling-related photos — not likely to happen anytime soon! No, I didn’t tire of posting in the series. I’m always ready to “talk trash.” (All right, keep the groans about my puns to a minimum!) No, between trying to clean the Temas Blog queue and deal with the many article ideas flooding my inbox lately (wish someone actually paid me to do this so I could do it full-time!), I had become stuck in “dead serious” all-substance, few-visuals mode. But time for a break, don’t you think?

As you might imagine, being an amateur “garbologist” (what those of us obsessed with studying waste sometimes call each other), I have visited several dumps, landfills, compost stations and recycling operations. I could regale you with many photos of trash heaps and informal dumps, wastepickers and their families going through them to pull out recyclables they can sell, or compost heaps. But then, if you’ve ever read a report or news item on waste in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), chances are good that such photos are all you’ve ever seen, so you’ve unconsciously concluded that’s all there is to know about waste “management” in LAC.

Not quite. Well managed recycling operations and landfills do indeed exist in LAC — they are in a minority still, and they get far less press, but they do exist. Let me introduce you to one.

My friend Eng. José Henrique Penido (“Penido”), a waste expert well-known (and liked) throughout LAC who works for Rio de Janeiro’s sanitation entity, Comlurb, has for several years now urged me to take a tour of Metropolitan Rio’s Jardim Gramacho (usually just referred to as “Gramacho”) landfill. He’s quite proud of how Comlurb manages Gramacho, and with reason — Comlurb turned a potential ecological disaster into a near model landfill. But I’m getting ahead of myself…

Last April (2006) I finally accepted Penido’s offer, and he kindly arranged for Gramacho’s on-site manager, Eng. Lucio Alves Vianna, to personally brief me on the fill and take me around.

A Bit of Background

Gramacho is not actually in Rio — it is at Km. 4.5 on the Washington Luiz highway between Rio and Petrópolis, technically within the limits of the municipality of Duque de Caxias.* It previously had been an uncontrolled dump for Caxias and surrounding municipalities. The state took it over in the late 1970s, designated it to be the disposal point for Rio and later assigned Comlurb the task of managing it and bringing it up to acceptable environmental standards. The site is about 1.3 million square meters (m2).

Comlurb has gradually transformed Gramacho into a modern landfill (we can debate whether it is a controlled or sanitary landfill) that meets all the technical and sanitary norms set for waste disposal by the state environment agency, FEEMA, except one — it does not have an environmental license, and probably never will.

Comlurb has gradually transformed Gramacho into a modern landfill (we can debate whether it is a controlled or sanitary landfill) that meets all the technical and sanitary norms set for waste disposal by the state environment agency, FEEMA, except one — it does not have an environmental license, and probably never will.

This is not because of its environmental management standards, which are quite good, but rather because the state environmental licensing law says a landfill cannot be licensed within a certain radius of a mangrove swamp. Gramacho was started literally right next to a mangrove, and before Comlurb took it over, the dump was slowly killing the mangrove. Although Comlurb inherited the site and has made the best of it (including restoring the mangrove), it cannot get formal acceptance through an environmental license because of the technicality.

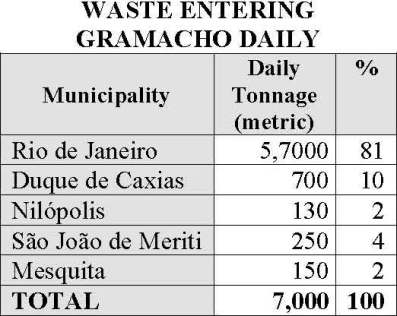

Gramacho has been scheduled to close for several years now, but until a replacement (“Paciência”) is fully up-and-running and licensed, Gramacho still receives about 7,000 metric tons of waste per day from not only Rio, but also Caxias, Nilópolis, São João de Meriti, Queimados, Mesquita and at times Petrópolis as well (see table).

If you click on the video at the right, you’ll see a history of Gramacho (in Portuguese) done by Comlurb, much of which features Penido.

If you click on the video at the right, you’ll see a history of Gramacho (in Portuguese) done by Comlurb, much of which features Penido.

Going Through Gramacho

Gramacho administrative offices. Photo: Comlurb

I wish I could show you the streets leading up to the main entrance to Gramacho, but the two pictures I took approaching the site came out too blurry. The surrounding streets were scruffy, shabby, primarily full of lots where various groups of wastepickers (known in Brazil as catadores) took their prized recyclables and recovered goods to be sorted.

By contrast the area inside the main gate to Gramacho was clean and neat, almost like an army base (see Comlurb photo at right).

Speaking in terms of environmental health of the catadores, health officials, from WHO and PAHO to national health authorities, always recommend not permitting them to work within the confines of a landfill, and UNICEF in recent years has had a program throughout LAC, but particularly in Brazil, to at least remove families and children from work in dumps and landfills.

Comlurb officials only allow a limited number (1,000-1,500) of catadores to enter and work “in an orderly fashion.” They must be registered and children are forbidden to enter and work the fill. Working within the fill is not healthy for the catadores, says Penido, but better than letting them go hungry. Most catadores probably would agree, and many complain that more are not allowed to enter and work as they wish.

Studies show that Gramacho’s biogas is about 50% methane and has a potential caloric value of 5000 kcal/Nm³. In 1996-2001 Comlurb experimented with biogas capture and use at Gramacho, at one point having some 300 wells extracting about 150,000 cubic meters (m³) per day.

The project was discontinued and at the time I visited the landfill the biogas station was closed, but this past December Comlurb put out a call for bids to capture and utilize the fill’s biogas and get carbon credits for it under the Kyoto Protocol’s clean development mechanism (CDM). Comlurb would receive 25% of any receipts collected from the concession. [I have to wonder, though, how any project involving Gramacho will receive carbon credits without the landfill having its environmental license.]

Surprising to me was how few birds I saw at this landfill. At many fills there are so many that it is like a dark cloud. In theory well-managed fills using proper coverage methods have few birds and low smell — Gramacho is probably the few landfills in LAC that I found that to be so.

A biologist/ecologist, Mario Moscatelli, was put in charge of helping restore the mangrove (manguezal), and he is assisted by several former catadores paid to tend it and allowed to crab there. Much of the mangrove’s wildlife was returned and prospered, particularly crabs. Comlurb has an interesting time series of pictures documenting the growth and health of the mangrove over time. It now forms a 130 hectare “green belt” around Gramacho.

In additional to all the sound ecological arguments for restoring the mangrove, there is also a practical one: it is a kind of failsafe mechanism for the landfill. Whatever little leachate escapes Gramacho’s collection and treatment system will pass through the mangrove, which is one of nature’s best water filtration systems, before reaching Guanabara Bay.

[That said, there is some concern among NGOs and state legislators that if Gramacho does not stop receiving trash and close soon, the landfill eventually may collapse or rupture in an environmental accident that releases massive amounts of contaminants into the mangrove and Bay, killing the former and badly polluting the latter. Or almost as bad, if it dumped enough into the nearby Rio Iguaçu, it might flood the area around the refinery on the other side of the landfill. Comlurb discounts the probability of such scenarios, saying that they monitor the landfill closely and have taken steps to minimize the risks.]

You can tour the mangrove preserve separately, entering from here, and school field trips do so frequently. The sign on the right announces that this is the entrance to a preserve for the mangrove “food source for marine life.”

The “TV Globo” network did a news piece awhile back on this preserve, which I include here (click the video below to play). It’s in Portuguese, but even if you can’t understand what’s said, the visuals are worth seeing.

Treatment of Gramacho’s Leachate

This an aerial view from Comlurb of the treatment area for the chorume (click to enlarge). At the top is the chorume “equalization lagoon” or pond.

This is a closer view of the equalization lagoon (click to enlarge). As beautiful as it may look in this picture, that may be nasty stuff you’re looking at. All too many landfills in LAC do not yet collect and treat leachate. Leachate can contain not only sediment and suspended organic material, but also salts, high concentrations of ammonia, and perhaps toxic chemicals and heavy metals.

I won’t bore you with a blow-by-blow description of the leachate treatment process.

— Keith R

* Caxais and Rio have had several battles about Gramacho, even though it was an ecological disaster before Comlurb took it over and in a 1970s agreement between state authorities and the municipalities at the time Caxais agreed to the siting of the fill. In 2004-5 the mayor of Caxais tried to impose an entrance tax on trash haulers entering the dump to raise revenue for the city. Comlurb diverted shipments to its smaller landfill at Gericinó rather than pay, and Rio won a court order for Caxais to desist from collecting the tax.

Tags: aeration tank, AIDIS, aluminum cans, ammonia, appliances, aterros, Baia de Guanabara, biogas, Brasil, Brazil, catadores, chorume, Comlurb, Duque de Caxias, equalization lagoon, FEEMA, garbologist, garrafas PET, Globo, Gramacho, greenhouse gases, Guanabara Bay, heavy metals, Kyoto Protocol, landfill, landfill gas, leachate, licença ambiental, lixo, mangroves, manguezal, mecanismo de desenvolvimento limpo, Mesquita, metais pesados, metano, methane, nano-filtration system, Nilópolis, Paciência, PAHO, papel, paper, PET bottles, Protocolo de Kyoto, Queimados, rellenos, residuos, Rio de Janeiro, São João de Meriti, tanque de aeração, tertiary treatment, toxics, UNICEF, waste

February 8th, 2007 at 9:33

Thanks for this terrific picture of what a good waste management project can be. It reinforced our sense of hierarchy in the world of carbon credits.While all options & technologies for clean,renewable fuels must be explored,waste-to-energy should be “1st among equals” solving multiple problems at one time.ACES relies on waste-to-energy as a creator of the carbon credits we use in our offsets programs for both consumers and business clients.While we know it is not a silver bullet,we’re not likely to run out of waste any time soon, so it’s a darn good place to focus — and you’ve shown us a great example.

February 8th, 2007 at 9:39

toxic waste is cool we should find a way to use it

February 8th, 2007 at 10:09

Virginia & Guy, welcome to The Temas Blog. Virginia, you’re probably the first WTE advocate I’ve met who doesn’t try to portray WTE as a silver bullet. 🙂

Guy, toxic waste is “cool”??? Is that what they teach at U-Mass these days?

This reminds me, though, of something I forgot to mention in the post. Gramacho does do elementary screening of trucks coming into the facility, and will turn away any determined to be bearing toxic wastes. Those must go to a special “secure” landfill operated under special license by a private firm (Bayer, if memory serves). Some hospital wastes are admitted to Gramacho, though.

Regards,

Keith

May 17th, 2011 at 21:03

What is the green foam in the aeration tank?

I really do want to know.

thanks,

Scott J. E.