« Coral Reef Protection III: What You Can Do | Home | Noteworthy Corporate Practices: Timberland in the DR »

Quantifying the Health Impact of Poor Environmental Management

By Keith R | September 6, 2006

Topics: Air Quality, Environmental Protection, Hazardous Substances, Health Issues, Occupational Safety & Health, Sanitation, Waste & Recycling, Water Issues | 1 Comment »

The Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO) recently released an interesting report on the linkages between environmental conditions and public health. It should be required reading for health, environment and aid officials and policymakers in all nations, but particularly in developing nations such as those in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). It certainly will be added to the Temas suggested reading list.

The Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO) recently released an interesting report on the linkages between environmental conditions and public health. It should be required reading for health, environment and aid officials and policymakers in all nations, but particularly in developing nations such as those in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). It certainly will be added to the Temas suggested reading list.

Huh? WHO? Involved in Environmental Protection?

It might come as a surprise to some readers that WHO involves itself with environmental issues, and some might question its involvement.

In my work for my former employer I handled most of the global environmental and health issues. I recall how many business executives, some government officials and privately even a few UN officials and NGO representatives groaned when health ministers at the January 1988 WHO Executive Board (EB) and May 1988 World health Assembly (WHA) debated the Brundtland Commission’s report on sustainable development, “Our Common Future.” Some seemed to think that the WHO had no business getting into environmental protection issues, that it “should stick to health.” A few even suggested that WHO officials could see what was going to be the UN system’s next overarching “mega-issue” and “wanted a piece of the action” (funding and attention).

Imagine what they said and hinted once WHO’s Director-General (DG) proposed and won approval for an “action plan” on environmental health the following year, and then created a special commission in 1990 on the issue to advise him!

I always thought WHO’s interest in the linkages between environment and health was not difficult to understand and I was not nearly as cynical about WHO’s desire to pursue it. Yes, maybe a little bit of the motivation behind the action plan and commission and their subsequent work products was to show that WHO had something relevant to contribute to the global debate on sustainable development, and maybe they wanted to capitalize on new interest in environmental issues to get funding for programs they otherwise might not have pursued.

I have always felt that their main motivations were never as shallow as all that. First off, any good epidemiologist, health historian, public health official or sanitary engineer can tell you that there are indeed evident linkages between the state of the environment and the health of the humans who live there. Many health epidemics in history can be traced back to environmental root causes. Furthermore, if you have contaminated drinking water or groundwater, people will have health problems associated to it. Use of banned pesticides, or misapplication or over-application of hazardous pesticides on agricultural produce can harm the health of the applicators, the pickers and the consumers who eat the end-products. Disposal of raw wastes in open-air dumps, or open-air burning of wastes, can cause a host of health problems. Heavy air pollution from particulates will cause lung problems. And so on.

In other words, it never took a rocket scientist to divine that the linkages existed. However, there had long been a debate among experts about

- just how much of an influence environmental conditions had on public health generally and specific conditions in particular;

- how much many of these conditions reasonably be addressed, particularly in the resource-strapped developing countries;

- what aid agencies and intergovernmental bodies such as WHO could do to make sure that the conditions that can be changed are indeed changed.

Tackling this debate was the crux of WHO’s action plan, and the commission appointed was intended to properly advise WHO on identifying state-of-knowledge, problems, contributing factors, trends, and possible policy and technology responses.

Second, one has to remember that in many countries the Health Ministry handles environmental issues, usually under a broad interpretation of mandate under the national Sanitary Code, until a framework environment law is passed and implemented and an environmental agency, secretariat or Ministry is created. This was particularly true in LAC, and in some LAC countries, still is the case today. Health Ministries saw the environment-health linkages in their everyday work, and it is the Health Ministers who largely control the agenda in the WHO.

Third, WHO already had a long history of involvement in environmental health issues. WHO served as the secretariat for multi-agency International Programme for Chemical Safety (IPCS). WHO had long worked with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in setting internationally respected pesticide residue limits. WHO had joined other UN agencies and the OECD in work on biotechnology safety issues. WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) constantly had to deal with environmental factors in its work in identifying and evaluating carcinogenic agents.

From There to Here

Subsequent to the adoption of the action plan in 1989, WHO has done some good work on environmental health that very much needed to be done, at least for the developing world, anyway. They helped establish environmental monitoring and surveillance networks. They set health criteria and guidelines — for such things as air and water contaminants, drinking water quality, proper management of hazardous wastes — and occupational exposure limits (for chemical, biological and physical agents) that are often copied, referenced or simply cut-and-pasted wholesale into national laws and regulations in LAC nations.

And last but not least, they set about trying to quantify the environmental determinants of health problems and what impacts they have on socioeconomic development. Without the availability of this knowledge base as foundation, it would be difficult for most health and environmental policy decision-makers in LAC nations to do their job in any meaningful fashion.

In recent years WHO studies have examined more closely the aggregate disease burden attributable to environmental factors at both the global and regional levels, trying to quantify in some fashion how many deaths and how much disease can be traced to factors such as unsafe drinking water, poor waste management, contaminated air, etc.

This latest study attempts to go a step further. The object of the study is to determine how specific diseases and injuries are influenced by environmental factors, and which country groupings and population segments are most vulnerable to such linkages.

Food for Thought: Some of the Key Findings of the Report

What did they find in this latest report, and how does it relate specifically to LAC?

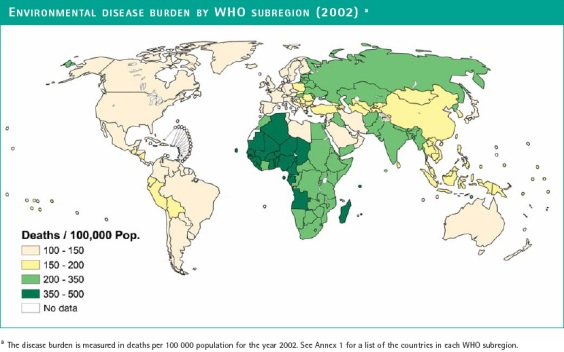

Well, the good news in broad-brush terms is that the environmental disease burden, as WHO likes to call it, is not as bad in LAC nations as it is in Africa, Central Asia and most of the former Soviet republics (Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, etc.). And with the notable exceptions of Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, Nicaragua and Peru (referred to collectively in the study as Americas, Group D – “AMR-D”), most LAC nations (“AMR-B”) are better off than China, southeast Asia and Eastern Europe (see WHO’s map above).

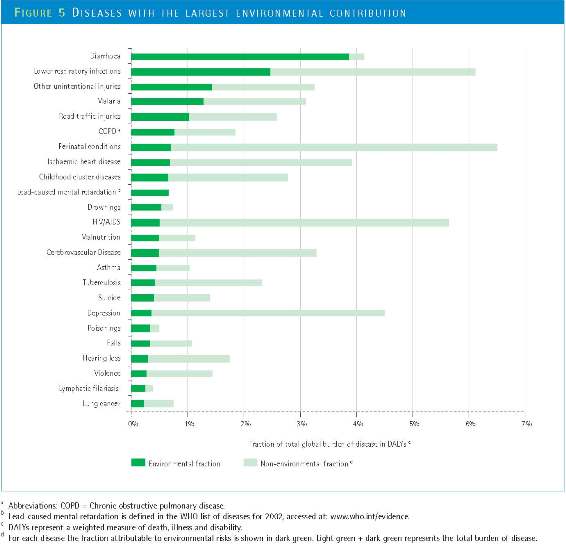

The report estimates that of the 102 major diseases, disease groupings and injuries tracked by WHO, 24% of the global disease burden and 23% of all deaths (premature mortality) can be attributed to environmental factors. The fraction of disease attributable to the environment varies according to disease conditions and by region. In most LAC nations, for example, the overall rate for attributable deaths is lower at 18%, although as high as 22% for AMR-D nations. However, for the disease category of all cancers, most LAC nations have a significantly higher rate than the global average: 16.1% instead of the global 10.6%.

The diseases with the largest absolute burden attributable to modifiable environmental factors identified were:

- diarrhoeal diseases at 94%, due to such risk factors as poor drinking water, sanitation and hygiene;

- lower respiratory infections at 42% for developing countries, due to mostly to indoor air pollution (particularly from household burning of coal, charcoal or wood);

- “other” unintentional injuries (occupational hazards, radiation, industrial accidents) at 44%;

- malaria at 42%, associated with policies and practices regarding land use, deforestation, water resource management, settlement siting, home drainage.

Who Suffers Most?

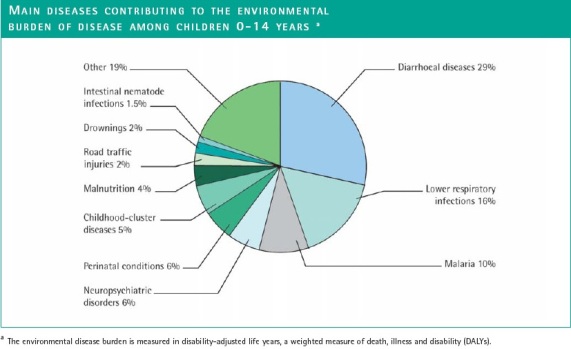

Not a big surprise here: children. The surprise comes in the magnitude. Among children 0-14 years of age, the environment-related portion of deaths is as high as 36%. The environmental portion of just the three biggest killers of children under 5 years of ago — diarrhoea, malaria and respiratory infections — are 26% globally! Children under 5 are five times as likely to lose their lives due to environment-related disease than the population as a whole. That’s just deaths! The study also found that children in developing nations were eight times more likely to lose healthy, productive life years than their counterparts in “developed” nations.

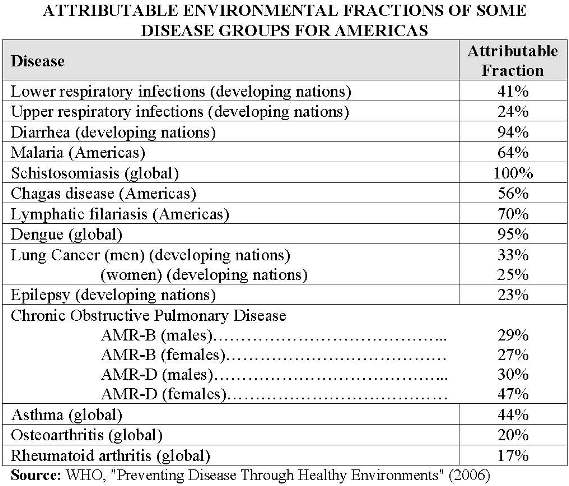

What are some of the diseases affecting LAC countries that are environment-linked? Well, check out the following table derived from the report:

What To Do with This Information?

The WHO report spends minimal time in suggesting what policy responses governments might take in response to the data and conclusions it presents. There is, of course, the now obligatory nod toward the UN’s Millennium Development Goals and fight to eradicate extreme poverty. But the report does include at least a few sensible “generic” suggestions, such as

- extending provision of clean drinking water and proper sanitation (sewage, drainage, water treatment, proper waste collection and disposal) services to as much of the population as possible, but particularly to educational facilities for children (thus minimizing time out of school due to environment-related health problems).

- good management of water bodies.

- providing cleaner cooking and heating systems to poor homes, to reduce health problems associated with indoor air pollution, and so kids do not have to spend time seeking firewood or other solid fuels.

- elimination of lead in gasoline (which, thankfully, has already been done in most LAC nations).

Of course, each nation needs to look at its own health profile and figure out which environment-linked disease burdens matter most, and which appropriate and cost-effective environmental interventions are needed to address them. For example, a LAC nation may no longer have lead in its gasoline and few of its homes used sooty solid fuels in cooking and heating, but its diesel buses and trucks still emit so many particulates that asthma and other respiratory diseases are rising significantly in its major metropolitan zones. For that country, measures targeting buses and trucks would make more sense.

Download the PDF version of the Report’s Executive Summary in English here.

Download the PDF version of the Report’s Executive Summary in Spanish here.

Tags: air pollution, Asamblea Mundial de la Salud, biological agents, biosafety, Biotechnology, biotecnologia, Brundtland Commission, buses, carcinogenic agents, carcinogens, Código Sanitario, contaminación atmosférica, diesel, disease burden, drinking water, environmental health, Environmental Protection, FAO, groundwater, hazardous waste, IARC, IPCS, medio ambiente, meio ambiente, occupational exposure, OCDE, OECD, particulates, pesticide residues, pesticides, physical agents, plaguicidas, poluição do ar, residuos, residuos peligrosos, resíduos perigosos, salud ambiental, salud pública, Sanitary Code, saude ambiental, solid fuel, trucks, waste, WHA, WHO

November 2nd, 2009 at 21:39

Hi, I found your article to be thorough, interesting and informative. Your article brings more awareness to readers in regards to worldwide Occupational Safety.

thanks,

Vincent J.