« The Other Side of the Cell Phone Revolution | Home | Coral Reef Protection III: What You Can Do »

Coral Reef Protection, Part II: The Current Situation

By Keith R | September 5, 2006

Topics: Environmental Protection, Marine/Coastal Issues | 1 Comment »

In the first part of my primer series on coral reefs in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), I examined why it is important to protect coral reef systems, what sort of things threaten their survival. Here in Part II, I look at what coral reefs LAC has, what condition they are in currently, and a brief overview of what currently is being done to protect and/or rebuild them. In Part III I’ll provide “eco-tips” on how divers, snorkelers and the average reader can help. Later blogs will look at individual groups working on the coral reef issue in LAC nations.

The Hidden Cities

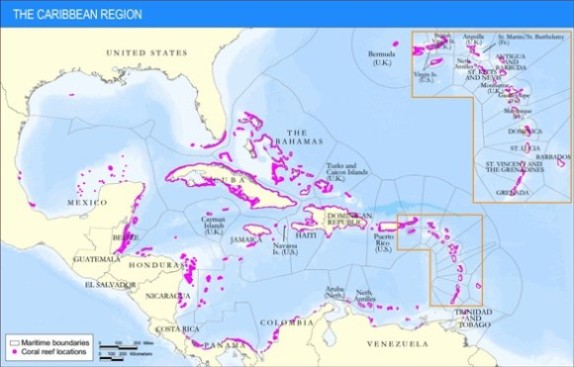

In "The Hidden Cities", a brief video actor Ed Harris narrates for one of the several groups working on reef protection worldwide, he calls coral reefs “the hidden cities” because of their size, complexities and number of inhabitants. The Caribbean Basin has a multitude of these “hidden cities” (see map), and there are also important reefs off the shores of Brazil and the Pacific coastlines of Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama and much of Central America.

There are four basic kinds of coral reefs: (1) fringing, which is always connected to the shore, no matter how far out to sea it extends; (2) bank/barrier, separated from the mainland by a lagoon and usually only reachable by boat; (3) platform, flat-topped (as the name suggests) formations usually far offshore in sheltered waters; (4) atolls, circular or nearly circular rings of coral reefs sitting on top of submarine mountains formed by former volcanoes. The Caribbean has mainly fringe, barrier and atoll. South America has mainly bank/barrier and fringe.

Source: "Reefs at Risk in the Caribbean" (2004)

The amount of coastline involved varies considerably. Some islands in the Caribbean Basin are nearly completely surrounded by coral reefs, whereas some of the South American nations have only small percentages of their coastline lined with coral reefs. Colombia, for example, has 1,700 km of coastline (both Pacific and Caribbean), but less than 150 km of that has coral reefs.

The Temas tool section has a listing of links to coral reef maps for many individual LAC nations at this link.

Assessment of the Current Risks to LAC Reef Health

As part of recent joint efforts by several organizations such as the World Resources Institute (WRI), World Conservation Union (IUCN), International Coral Reef Initiative , ReefBase and Reef Check to map coral reef health worldwide, and specific program for the Caribbean run by the UN Environment Programme's (UNEP) Caribbean Environment Programme (CEP), and other efforts supported by UNESCO and the World Bank, some initial assessments of the health of LAC coral reefs and threats thereto are available.*

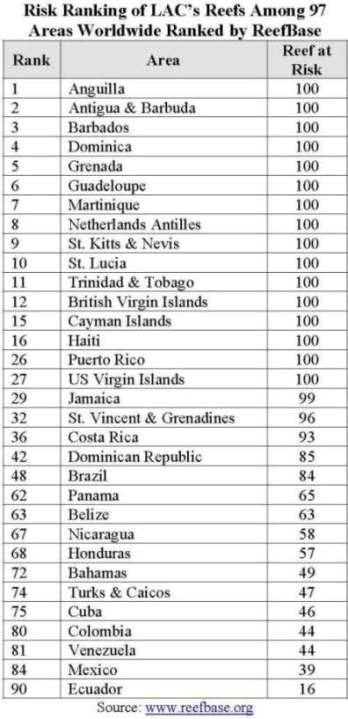

The news, overall, is not good. Among the 97 nations and territories worldwide with coral reefs assessed by Reefbase (see table), 29 are in the LAC region. In fact, 16 of the 28 nations/territories with 100% of their reefs at risk are in the Caribbean Basin, followed closely by Jamaica, St. Vincent and Costa Rica. Only seven LAC nations have less than half of their coral reefs at risk.

There is clearly much work to be done.

Some of the ones in decent condition tend to be far offshore or fall within coastal/marine protected areas (MPAs) created by law. But so far being in an MPA is no guarantee of protection: LAC has many of them already. Mexico has 28 protected areas that contain coral reefs, Central America and Panama 36, the Eastern Caribbean (mostly Lesser Antilles) 63, non-US "Northern Caribbean" (Bahamas, Caymans, Cuba, DR, Jamaica, Turks & Caicos) 70, and South America 20. But many of these are not well monitored, patroled and enforced, and many are seriously over-fished or threatened by irresponsible tourism practices.

The main threats vary subregion to subregion, country to country, reef to reef, of course. In 2004 report "Reefs at Risk in the Caribbean," WRI ranks threats in four main categories:

a. poorly planned and/or managed coastal development — not only from mass tourism, dredging, pier and port construction, but also from new communities sprouting up along the coastline without proper waste management and sanitation services. Also affecting coral reefs is construction allowed in the sensitive mangrove and wetland areas that serve as natural sediment traps; without them, increased sediment and algae growth due to nutrient run-off smother coral reefs.

b. sedimentation and pollution from inland sources. While this can include several sources, experts suggest that the main culprits are poor agricultural practices and deforestation.

c. marine-based pollution (ships, oil rigs, etc.).

d. overfishing and poor or illegal fishing practices.

The leading "high" threat to the Southern Caribbean zone is overfishing, whereas in the "Continental Southwestern Caribbean" zone it is sedimentation. If one combines "medium" and "high" risks, in the Southern Caribbean there is a tie between overfishing and coastal development at about 45%, whereas in the SW Caribbean it is roughly a tie between overfishing and sedimentation at around 70%.

What Is and Isn't Being Done Already

There are a number of positive steps that have been taken to help LAC reefs, but as in so many environment issues facing the region, it seems that for every positive there is a caveat or counterbalancing force — a sort of Good News, Bad News situation:

The good news is that region has already created many Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). However, the bad news is that most are not well monitored, supervised and managed by environment authorities, and many are under threat from unsustainable fishing. And some nations — most notably Venezuela — lack laws explicitly and strongly protecting coral reefs.

The good news is that region has already created many Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). However, the bad news is that most are not well monitored, supervised and managed by environment authorities, and many are under threat from unsustainable fishing. And some nations — most notably Venezuela — lack laws explicitly and strongly protecting coral reefs.- The good news is that several LAC nations, with the help of international agencies such as the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as Reef Check and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), are doing a status check on their reef systems and an inventory of that system's biodiversity.

- The bad news is that the process is slow and large data gaps remain. This is one area where average divers can help, by volunteering for a Reef Check team. [More on this in an upcoming blog.]

- The good news is that the types of fishing practices most threatening to reef health (dynamite fishing, use of bleach, etc.) are banned by national laws in the region. The bad news is that is that they are poorly enforced, if at all. In some countries, such as the DR, offending fisherman are spared enforcement actions because they cooperate with naval and drug enforcement officials in interdicting drug shipments.

The good news is that in some nations, the extraction of any type of coral, sponges, gorgorians, sea stars, urchins, mollusk shells or any other part of a coral reef system, living or not, is explicitly banned by law. The bad news is that, clear regulatory bans are not universal, many ordinary residents and tourists do not realize the extent of such bans, and they are often not enforced. How many of you have bought "souvenir" coral or sponges or urchin shells while vacationing in the Caribbean?

The good news is that in some nations, the extraction of any type of coral, sponges, gorgorians, sea stars, urchins, mollusk shells or any other part of a coral reef system, living or not, is explicitly banned by law. The bad news is that, clear regulatory bans are not universal, many ordinary residents and tourists do not realize the extent of such bans, and they are often not enforced. How many of you have bought "souvenir" coral or sponges or urchin shells while vacationing in the Caribbean?- The good news is that some nations have integrated their diverse agencies and authorities handling reef and coastal management so as to minimize bureaucratic conflicts and make policy formation and implementation more coherent. The bad news is that many haven't, and those that have still do not have the staff and other resources needed to do their jobs properly and fully.

The good news is that multilateral lenders now are funding efforts by governments to improve waste management and sanitation services and standards in their coastal zones. The bad news is in some areas the damage may have already been done to the nearby reefs, and not enough countries are seeking such loans.

The good news is that multilateral lenders now are funding efforts by governments to improve waste management and sanitation services and standards in their coastal zones. The bad news is in some areas the damage may have already been done to the nearby reefs, and not enough countries are seeking such loans.- The good news is that some resorts are joining efforts to help protect and restore reefs. For example, the Dominican resorts that won the Blue Flag eco-certification in Bayahibe have supported Reef Check teams, supported a reef ball project, put in reef-friendly boat mooring and supported training for boat operators on proper conduct regarding the nearby reefs. Blue Flag standards require beach communities to support protection of any nearby reefs. [More on Blue Flag in a future blog.] The bad news is that many hotels near reefs are not yet persuaded it is in their long-term interest to help protect the reefs, and that some of LAC’s reefs do not have such possible patrons near them.

What the Experts Tend to Recommend

What the Experts Tend to Recommend

Just as the challenges each reef vary, so do the recommended policy responses. But generally speaking, experts tend to recommend the following set of actions:

- promote environmental education on marine and coastal issues, at all levels of society;

- complete assessments of the status of all reefs and maintain regular monitoring at key sites;

- involve all stakeholders — communities, tourism businesses, fishermen, boaters, etc. — in the planning and management of coastal sectors;

- seek sustainable funding measures for supporting the Marine Protected Areas;

- reduce sedimentation by promoting good agricultural practices (e.g., terracing, more responsible use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers, etc.);

- impose tighter control on coastal construction through strict enforcement of environmental impact assessment (EIA) and zoning rules;

- improve protection of mangroves and coastal wetlands;

- promote sustainable fishing practices, enforce current fishing restrictions, create fish replenishment reserves and require licensing for fishing;

- train more technicians to become reef and coastal management inspectors and provide with better equipment and support;

- recruit local community leaders as environmental wardens, to promote both education about the importance of caring properly for reef ecosystems and to assist in enforcement;

- decrease or eliminate untreated sanitary and solid waste discharges in all coastal areas;

- improve and enlarge reforestation programs in upper and medium watersheds;

- promote good environmental business practices in the tourism industry along the coasts, perhaps through promotion of such certification schemes as Blue Flag and/or Green Globe.

— Keith R

*Lauretta Burke and Jon Maidens. Reefs at Risk in the Caribbean. 2004. Published by World Resources Institute (WRI). http://pdf.wri.org/reefs_caribbean_full.pdf

D. Linton et al., "Status of Coral Reefs in the Northern Caribbean and Atlantic Node of the GCRMN," in Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2002 . C. Wilkinson, ed. (Townsville: Australian Institute of Marine Science, 2002).

Tags: algae growth, América Central, Bahamas, barrier reefs, Bayahibe, Blue Flag, Brasil, Brazil, Caribbean Basin, Caribe, Cayman Islands, Central America, Chile, coastal development, Colombia, coral, coral bleaching, coral reefs, Costa Rica, Cuba, deforestation, divers, Dominican Republic, dredging, eco-certification, Ecuador, EIA, gorgorians, IUCN, Jamaica, Lesser Antilles, manglares, mangroves, marine protection areas, marine-based pollution, mass tourism, mollusk shells, oil rigs, overfishing, Panama, piers, PNUMA, ports, reef balls, Reef Check, reef protection, Reefbase, reflorestamento, reforestation, República Dominicana, sea stars, sedimentation, ships, snorkeling, sponges, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, sustainable fishing, The Nature Conservancy, Turks and Caicos, UNEP, UNESCO, urchins, Venezuela, waste management, watersheds, wetlands, WRI

July 24th, 2013 at 4:30

Coral reef protection is so important for the continuation of Caribbean tourism. I actually believe the hotels and airlines have a major part to play in education their guest and passengers as to the dangers it faces. Hopefully the message will get through sooner rather than later.