« Eco-Help for the Cold Chain | Home | Eco-Certification for Tourism: The Role of Blue Flag, Part I »

WHO to Policymakers: Clear the Air

By Keith R | October 12, 2006

Topics: Air Quality, Environmental Protection, Health Issues | No Comments »

Last week the World Health Organization (WHO) challenged governments worldwide: save millions of lives by tightening your air quality standards.

Last week the World Health Organization (WHO) challenged governments worldwide: save millions of lives by tightening your air quality standards.

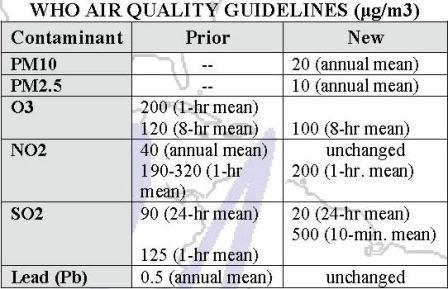

WHO issued the challenge while releasing the first major overhaul of its widely-observed Air Quality Guidelines (AQGs) since 1997. WHO first released AQGs in 1987 in response to requests from governments for some guidance on what standards to set for particular airborne contaminants based on scientific assessment of their health impacts, using technical studies and epidemiological data. The “global” version of the AQGs were updated in 1997, although WHO’s European Office (EURO) has been working on scientific assessment and updating the guidelines for regional use since then. This new version of the AQGs relies heavily on EURO’s work. Unlike prior AQGs versions, this one addresses all regions of the world and attempts uniform targets for air quality (rather than ranges “based on local conditions,” as were previously used for some contaminants).

So What?

Why do the WHO AQGs matter in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) context?

Because many, if not most, LAC governments look to the WHO AQGs as the basis for national norms — in the past, some have simply adopted them wholesale. To provide just one example of their influence: Peru’s new General Environment Law requires that WHO standards be used as reference when setting air quality standards (ECAs) and Maximum Permissible Limits (LMPs).

As such, the new AQGs pose a significant challenge to LAC policymakers, because they dramatically lower standards for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2), tighten standards for ozone (O3) and for the first time set global standards for large (10 microns in diameter or smaller) and fine (2.5 microns in diameter or smaller) particulate matter — and while doing so, set particulate standards substantially tougher than those in place in most LAC nations.

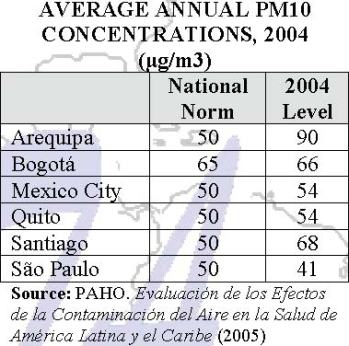

Take, for example, the AQG for large particulates (known as PM10). Most LAC nations, if they have set an air quality norm for PM10, set it at an annual arithmetic average of 50 ?g/m3 (the notable exception is Colombia, which currently has it set at 65 ?g/m3 but under a new norm will lower it to 50 ?g/m3 by 2011). Even at that level, very few major LAC cities comply with the existing norm (see chart). WHO now is calling for an annual mean of 20 ?g/m3, which would mean at least a halving of large particulate emissions in São Paulo and a 4-5 times reduction in Arequipa, Peru.

In most cities the principal source of PM10 emissions are from vehicles — 56% in Santiago de Chile, 61% in Mexico City, 64% in Buenos Aires, 66% in Lima, according to a recent Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) report (see the Temas Recommended Reading List). Thus adopting the new WHO standard would mean that LAC policymakers would have to substantially crack down on vehicle emissions, particularly diesel-powered vehicles. In many cases, this means an expensive refitting or replacing their fleet of municipal buses.

WHO argues that adopting and enforcing this one standard could reduce annual urban air pollution by as much as 15%, in the process saving millions of lives. As noted in the recent WHO publication on health consequences of poor environmental management profiled here, there are substantial health impacts of poor air quality.

“By reducing air pollution levels, we can help countries to reduce the global burden of disease from respiratory infections, heart disease, and lung cancer which they otherwise would be facing,” said Dr Maria Neira, WHO Director of Public Health and the Environment, upon releasing the new AQGs. “Moreover, action to reduce the direct impact of air pollution will also cut emissions of gases which contribute to climate change and provide other health benefits.”

The new AQG for fine particulates (PM2.5) also will require revisions in most national air quality standards. Many nations (such as Brazil, Chile, Nicaragua and Peru) do not yet have separate PM2.5 norms. Those that do have them set them much higher than WHO’s latest recommendation. Mexico, for example, recently lowered its annual norm for PM2.5 to 15 ?g/m3, but WHO now recommends 10 ?g/m3.

The cut in ozone levels suggested by WHO, while more modest on paper, will prove difficult for most LAC cities to achieve. Ozone is a key component in photochemical smog, the effect most average citizens associate with air pollution. Ozone levels tend to be high in cities with large numbers of sunny days throughout the year, as many LAC cities do. High ozone levels are associated substantial respiratory problems and asthma attacks (thus the public warnings to asthmatics living in US and European to stay indoors on days with high O3 levels detected).

The new SO2 levels are substantially lower that those in most LAC nations. Chile and Peru, for example, set their annual exposure at 80 ?g/m3, so they will have to cut current levels fourfold to come in line with WHO guidelines (not a simple feat for Santiago!). WHO argues that the lower levels are needed because recent studies indicate greater health impacts at lower levels than previously thought, and that the regulatory steps to lower SO2 levels tend not to be as costly as those for some of the other contaminants.

Although WHO did not cut the annual mean for NO2, it did tighten the one-hour mean and that will mean substantial cuts in routine emissions in places such as Lima. WHO notes that many cities do not meet even the current annual mean for NO2 of 40 ?g/m3 — that is certainly true for many LAC cities. In fact, Peru’s current official NO2 standard is 2 1/2 times higher (although actual levels measured at the center of Lima have been trending downward and finally dipped under 40 ?g/m3 this past July).

The PDF of the new AQGs are available in both English and Spanish.

— Keith R

Tags: air pollution, Air Quality, air quality guidelines, AQCs, Arequipa, Argentina, Buenos Aires, calidad del aire, Chile, Colombia, contaminación atmosférica, contaminación del aire, ECA, Lima, LMPs, Mexico, Mexico City, Nicaragua, nitrogen dioxide, NO2, O3, OMS, ozone, particulates, Peru, photochemical smog, PM10, PM2.5, poluição do ar, qualidade do ar, Santiago, São Paulo, SO2, sulfur dioxide, vehicle emissions, WHO