« Progress Toward MDGs in Water in LAC | Home | Update: Tetra Pak & Aseptic Packaging Recycling in Paraná »

Progress Toward MDGs in Sanitation in LAC

By Keith R | August 17, 2008

Topics: Health Issues, Sanitation | No Comments »

One of my first posts here on The Temas Blog concerned the 2006 World Health Organization (WHO) progress report on reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) regarding drinking water and sanitation. So it’s probably fitting as I approach the second anniversary of the The Temas Blog to be discussing the latest update just released by the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) run by both WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). It’s even more fitting to be discussing sanitation, since 2008 officially is the International Year of Sanitation (IYS).

One of my first posts here on The Temas Blog concerned the 2006 World Health Organization (WHO) progress report on reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) regarding drinking water and sanitation. So it’s probably fitting as I approach the second anniversary of the The Temas Blog to be discussing the latest update just released by the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) run by both WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). It’s even more fitting to be discussing sanitation, since 2008 officially is the International Year of Sanitation (IYS).

I’m discussing this report in two posts – in Part I, I looked at the water portion; here in Part II I address the sanitation side.

Like its predecessor, this report provides a good snapshot not only of where things stand worldwide, but also of where international lending and aid agencies are likely to focus their water/sanitation programs in the next 10 years. The latest report, however, also includes new and interesting types of data not explored in the prior one. So I am adding to the Temas Reading List for water and sanitation.

A Word First About What Does and Doesn’t Count in the Access Figures

The Millennium Project’s Task Force on Water and Sanitation defines basic sanitation as “the lowest-cost option for securing sustainable access to safe, hygienic and convenient facilities and services for excreta and sullage disposal that provide privacy and dignity while ensuring a clean and healthful living environment both at home and in the neighborhood of users.”

The trouble is how to measure these, particularly with the principal tool utilized, household surveys. So instead what is measured and reported upon is “improved” access to sanitation facilities. JMP defines “improved” sanitation as facilities that ensure hygienic separation human excreta from human contact, including:

- flush or pour-flush toilets/latrines to (a) a piped sewer system; or (2) a septic tank; or (3) pit latrine;

- a ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrine;

- pit latrine with slab;

- composting toilet.

The JMP divides the rest into three categories:

The JMP divides the rest into three categories:

- facilities that might otherwise be considered as “improved,” but since they are shared between two or more households JMP only labels them as “shared”;

- “unimproved,” which includes bucket latrines, hanging latrines and pit latrines without slabs; and

- open defecation (defecation in fields, forests, bushes, bodies of water, etc.). Open defecation is bad news, since it puts the whole community at risk of diarrheal diseases, worm infestations and hepatitis.

LAC in the Global Context

According to the JMP report, only 62% of the world’s people (only 53% in the developing world) have access to an improved sanitation source, 8% used shared facilities, 12% use “unimproved” facilities and 18% practice open defecation. The one big piece of good news JMP stresses on the sanitation front is that open defecation is falling. The bad news is, though, that without dramatic measures much of the world will miss the sanitation MDG targets.

Among all developing nations, coverage in urban areas averages 71%, and in rural areas 39%.

The total “improved” sources figure for LAC as a region in 2006 is 79%, meaning that, as a region, LAC is ahead of the intermediate target for 2006 it needed to achieve (78%) on the way to reach the 2015 regional target, 84%. That said, 121 million LAC residents still lacked access to “improved” sanitation in 2006.

The total “improved” sources figure for LAC as a region in 2006 is 79%, meaning that, as a region, LAC is ahead of the intermediate target for 2006 it needed to achieve (78%) on the way to reach the 2015 regional target, 84%. That said, 121 million LAC residents still lacked access to “improved” sanitation in 2006.

The aggregate “improved” figures masks many trouble spots. Five nations — Bolivia, Guyana, Haiti, Nicaragua and Suriname — are substantially off-track (more than 10% below their MDG target), while Jamaica is mildly so (5-10% below target).

As a region, LAC does better than the developing nations as a group in coverage for both urban (86% instead of 71%) and rural areas (52% instead of 39%) areas.

Shared facilities are not as prevalent in LAC as a whole: 6% in urban areas, 4% in rural. Use of unimproved facilities in LAC as a whole stands at 21% in rural areas but only 6% in urban areas. Open defecation is still found in LAC rural areas in high numbers (23%), but not so much in urban zones (2%).

A Closer Look at the LAC Picture

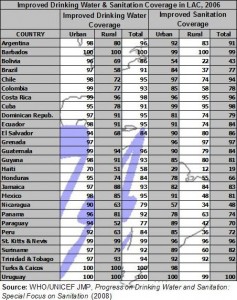

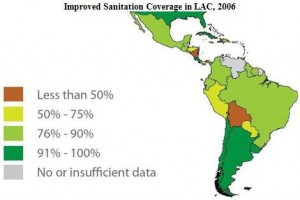

As the map graphic at right from the report makes clear (click on the image to see a larger version), improved sanitation coverage in LAC is a mixed bag. A few LAC nations — Argentina, Barbados, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay — have 91% or higher overall access for “improved” sanitation.

As the map graphic at right from the report makes clear (click on the image to see a larger version), improved sanitation coverage in LAC is a mixed bag. A few LAC nations — Argentina, Barbados, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay — have 91% or higher overall access for “improved” sanitation.

Slightly more are in the 76-90% zone. Honduras and the 3 P’s — Panama, Paraguay and Peru — are in the 50-75% zone, and rounding out the bottom rung are Bolivia (43%), Haiti (19%) and Nicaragua (48%). Haiti is a particularly tough case: 162,000 Haitians have actually lost access to improved sanitation since 1990.

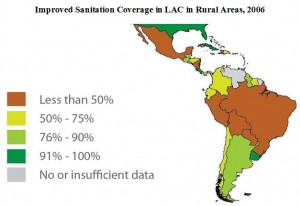

Notable is the divide between urban and rural coverage for drinking water. As you can see in the graphic at right (click to see a larger version), average improved sanitation coverage in urban areas tended to be much higher that the overall average in each nation.

Why is that? Because of poor showings on the rural side (click on image to view a larger version). Generally speaking, coverage in urban areas is 10-20 percentage points higher than in rural areas.

The biggest national divergences between urban and rural in LAC? Peru with a 49 percentage point difference between urban and rural, followed by Brazil and Paraguay both with a 47 point gulf, and Mexico with 43 point gap.

The biggest national divergences between urban and rural in LAC? Peru with a 49 percentage point difference between urban and rural, followed by Brazil and Paraguay both with a 47 point gulf, and Mexico with 43 point gap.

But How Much Progress is That on Sanitation?

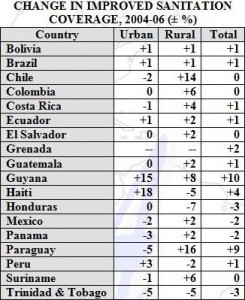

I was curious about something the report does not address: progress since the last update (in 2006, using 2004 data). The new report discusses who’s making progress or not — but only in terms of comparing current numbers with those of the 1990 baseline, or to the goal set for 2015 under the MDG process. I want to know how things have been going in the short term.

So I went back and dug up the 2004 data and compared it with the 2006 figures. I did so thinking I would find almost no change in the total figures for each country, probably little change in the urban figures, and perhaps a few modest changes in the rural numbers.

So I went back and dug up the 2004 data and compared it with the 2006 figures. I did so thinking I would find almost no change in the total figures for each country, probably little change in the urban figures, and perhaps a few modest changes in the rural numbers.

But the figures actually produced some surprises. Seen through this optic, Guyana and Haiti have made impressive gains on the urban front in just two years (see table); Chile, Colombia, Guyana, Paraguay and Suriname have done so in the rural; best improvement overall goes to Guyana at 10% in just two years, followed by Paraguay at 9%.

Slightly surprising were the sharp drops (-5 percentage points) in urban coverage in Paraguay and Trinidad and Tobago, and the smaller urban drops in Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico and Panama. My guess? That the poor neighborhoods of the major metropoles in these countries grew but sanitation services did not keep pace.

As for drops on the rural side, I was not surprised at Haiti, but was truly puzzled at the 7-point drop in Honduras (is that due to the hurricane damage?), the 5-point drop in Trinidad and Tobago (what’s the stroy there?) and 2-point drop in Peru.

Shared Sanitation and Open Defecation

As noted above, LAC as a region has relatively low levels of shared sanitation. But it is far more prevalent in a few LAC nations. For example, Bolivia and the Dominican Republic both have 15% of total households using shared sanitation. 23% of Haitian urban households use shared facilities (19% share facilities between 2-5 families). 16% of Jamaican urban households and 13% of their rural households use shared sanitation.

Where in LAC is open defecation still practiced the most? According to JMP data, it’s Bolivia at 26% overall (54% in rural zones), followed by Honduras at 16% overall (28% in the countryside) and Peru at 10% overall (35% in the countryside). LAC nations which used to have large percentages practicing it but no longer do (i.e., a dramatic change in practices) include El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico. Brazil, while having only has 9% overall practicing it, has 40% levels in rural areas and the number of people involved is among the world’s largest at 18 million.

Lots of Work Yet to be Done

What the JMP progress report shows is alot of work yet to be done on the sanitation MDGs in LAC.

And I am not just speaking of the six aforementioned nations officially not “on track”, although even there I must wonder aloud, with so many multilateral banks and bilateral aid agencies willing to fund sanitation improvements in LAC (there are many examples here in the pages of The Temas Blog, just click on “sanitation” in the “Categories” drop-down menu in the left-hand column, or click on the “sanitation” tag below this article), why are these nations as far behind as they are.

I also cannot understand why, in a mass communication age and with all the advances that have been made in health education and communication, can there be figures so high in LAC on open defecation? Changing this is doable and not necessarily costly and should have be taken care of long ago. Heck, the UN even provides ready-made posters, fact sheets, talking points, etc. in several languages on its IYS website, and the WHO, UNICEF and World Bank (not to mention USAID, SIDA, etc.) have educational materials and studies on what makes an effective communication strategy.

I also cannot understand why, in a mass communication age and with all the advances that have been made in health education and communication, can there be figures so high in LAC on open defecation? Changing this is doable and not necessarily costly and should have be taken care of long ago. Heck, the UN even provides ready-made posters, fact sheets, talking points, etc. in several languages on its IYS website, and the WHO, UNICEF and World Bank (not to mention USAID, SIDA, etc.) have educational materials and studies on what makes an effective communication strategy.

Nearly the same can be said of bringing up the numbers in “improved” sanitation. After all, the bar was not set so high. As WHO Director-General Margaret Chan said at the release of the JMP report, “We have today a full menu of low-cost technical options for the provision of sanitation in most settings.”

If nearly every LAC household now without “improved” sanitation can be given a composting toilet or improved pit latrine, the MDG would be met. Countries don’t have to spend billions on laying new sewer pipelines. However, politicians tend to find such projects sexier because of the sums involved (and perhaps more graft and bribery opportunities?) and high visibility. Besides, what politician would prefer to be pictured in the local newspaper next to a composting toilet rather than next to heavy machinery laying heavy pipe?

Tags: alcantarillado, Barbados, Bolivia, Brasil, Brazil, bucket latrines, composting toilet, diarrheal disease, flush toilets, Guyana, Haiti, hanging latrines, health communications, health education, hepatitis, International Year of Sanitation, IYS, Jamaica, JMP, Margaret Chan, MDGs, Millennium Development Goals, Nicaragua, OMS, open defecation, Paraguay, Peru, pit latrine, public health, salud pública, saneamento, saneamiento, Sanitation, saude, septic tank, sewer connections, sewer system, Suriname, UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, worm infestations